What is a brand?

Imagine you enter a bank, ask for an account statement to see how much money you have, and the clerk says something like:

“Your money – well, you see, your money is like a gut feeling I have about your worth.”

And when you express bewilderment, she goes on –

“Yes. If I think you’re rich, judging by your clothes, for example, then here at the bank we credit your account.”

“But…“

“Money is an interface between the bank and you, an idea I have in my mind about your assets.”

“…?”

Scratching your head? Fortunately, a scene like this never happens. If you go to a bank, you trust that all employees have a common understanding of what “money” means. If you go to a hospital, you strongly hope that all doctors will have an aligned understanding of what “disease” means. In general, we expect professionals to share a common view of the fundamentals of their trade.

This is not true in branding. Experts do not share a common view of what “brand” means. They call it everything from a gut feeling, a living memory, an interface, to an intangible sum of attributes, or a business asset. To confuse matters further, many are using “brand” when they actually mean something else (e.g., company, or image). (1)

There is one definition for “profit” and at least 30 for “brand”. If you were a CEO, what advisors would you spend your money on, factually sounding economists or metaphorically convoluted “brand consultants” who don’t seem to know what exactly they’re talking about?

Interesting enough, leading economists have been getting it wrong for decades - yet people still trust them. “Brand fluff people” have been intuitively getting it right for decades – yet people still don’t trust them (2). It is an impressive example of how powerful and important a well-defined vocabulary is.

Us branding professionals can take part of the blame. Instead of defining the fundamental term of our profession in a straight-forward way and derive robust implications with rigorous backing, we each create our own individual metaphor when talking about brand, often using a description for a definition (to name just one mistake). The lack of a commonly accepted solid foundation for our profession makes the discourse unprecise at best and illogical at worst, a barrier to gaining trust with senior management in many companies.

Definition

So, what is a brand? Let’s start with the origin and the historical evolution of the word’s meaning.

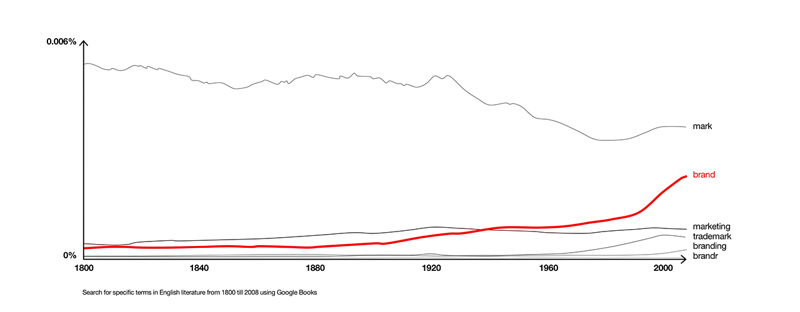

For thousands of years (3), people used engraved or burnt-in signs to identify goods as their own. Two words emerged to describe this action and its result – the Greek-derived marking / mark for engraved or painted symbols (for example for ceramics or tea, early traded goods) and the Old Norse-derived branding / brand for burnt-in symbols (for example for domestic animals). In time, mark established itself in German, Italian, French, while brand became the generic term for “marking” in English (4). It is only relatively recently that the usage of brand increased – if we look at frequency in Google-digitized books, as an illustrative and not exhaustive example, the word “brand” started to be used (in writing) more frequently at the beginning of the 20th century and increased sharply only starting with the 1980’s and the dawn of brand consultancies.

But what do, or rather what should the terms brand and branding mean? Livestock branding has had the same unambiguous meaning from its appearance as a term. In time, as interactions between buyers and sellers diversified, in order to identify their goods, sellers went beyond “burning” visual signs, using colors, textures, smells, but also words, phrases, behaviors, rituals, carried out across multiple touch points, to identify their goods (and services) as theirs.

This is the original, unambiguous purpose of branding: identify a product or service as belonging to a certain entity. The corresponding definition of branding is therefore “everything an entity does with the intention to be recognized”. A “livestock brand” is the symbol used for recognition (you can still find “community brand walls” in the American West). Keeping with the original meaning, a modern brand remains the result of the branding activity, only now incorporating many different kinds of intentional expressions:

A brand is the sum of all expressions by which an entity (person, organization, company, business unit, city, nation etc.) intends to be recognized.

That’s it. Not more, not less. A definition does not have to inspire or guide. The definition of life also doesn’t provide guidance how to live. The definition of football is quite dull, but what wealth of emotion is triggered by playing and watching it!

We see no reason to change the meaning of an unambiguous term with something more ambiguous. Doing so adds cognitive load, increases potential for confusion and makes common understanding more difficult – as we see with brands and branding.

Language evolves, and a word’s meaning may change over time, but the only good reason to switch to a new meaning of a word is that it is being used quasi-unanimously in reality and is equally unambiguous as the original. This is not the case with most definitions of “brand” floating around the industry. They add concepts like image, promise or experience to the meaning of brand – which is superfluous and, we believe, counterproductive. The (etymo)logically derived modern definition of the ancient term as presented above has an important enough role in current economic reality and should not need additional bells and whistles to command due attention.

Ambiguity test

A definition functions in much the same way as the foundation of a house. It stays under the surface, may not be particularly attractive, but it ensures the stability of the whole building. It almost never becomes a subject of conversation again – unless it is shaky.

To ensure our definition is not shaky, we have applied two tests: Biconditionality and Occam’s razor.

Biconditionality (“If all A=B, all B=A”) helps distinguish between descriptions and definitions. For example, “an uncle is a brother of a parent – all brothers of all parents are uncles”.

Occam’s razor contains two principles: Plurality (“Plurality should not be posited without necessity”) and Parsimony(“Among competing hypotheses, the one with the fewest assumptions should be selected”). (5)

By combining these tests, we get to three criteria we can run any definition against:

1. A definition should allow no exceptions – if a brand is “something”, then all “somethings” are brands

2. If there is already a word for what we are trying to describe, there’s no need to call it something else (e.g., don’t call “image” “brand”)

3. Use as few elements as possible in the definition, but as many as necessary

Feel free to challenge every definition of brand you see – including the one proposed in this article – along these criteria. For example: Defining brand as an interface, or business asset, is not enough. Not all interfaces and not all business assets are brands. Another example: Jeff Bezos famously said “a brand is what people say when you’re not in the room”. There is already a word for that – reputation. Sorry, Jeff, your definition is cool, but not accurate.

Taking the pill ourselves: are all “sums of expressions through which an entity wants to be recognized” brands? Yes. Also, take any word away, and the definition loses its meaning or becomes insufficiently precise, while any additional word would be redundant or add unnecessary elements.

Challenges

“Wait a second. Surely, a brand means more than that. Recognition, ok, but what about persuasion, loyalty? Brands are surely about promises too, and reputation.”

Persuasion and loyalty are not driven exclusively by the brand, and therefore should not belong in the definition (Occam’s Razor: the one with the fewest arguments is the best). Business model, marketing tactics, environmental constraints all influence persuasion and loyalty, with or without branding. It is recognition that branding is about. That being said, if done well, branding can influence persuasion and loyalty, through providing orientation, fostering trust, enabling self-expression (“we are what we buy”).

Every entity creating expressions with the intention to be recognized (pretty much every commercial entity and every person we know) has a brand. That alone is not enough to be successful though. Brands serve recognition, for better or worse. It is strong brands that help with persuasion and loyalty, leading to a substantial increase in economic value above a “baseline” business.

What about promise and reputation? A promise is a prerequisite of a strong brand, part of the branding strategy. Reputation and image on the other hand are influenced through branding, but also by other factors, which are not branding-influenced (competition, market changes etc.). Neither should be part of the definition of brand.

What about brands vs. trademarks? Trademark is a legal term to describe a protected intangible asset. Brands include expressions that cannot be classified as physical “markings”, including expressions that serve recognition but are not protectable as trademarks (for example, the way a person speaks can be recognizable (think of Martin Luther King, or… Donald Trump), but currently cannot be registered as trademarks. (Should they?)

Implications

So what? What does this mean for us as branding professionals? What should we do differently?

Clarity of thought: A solid definition helps clarify which of a company’s actions can be classified as “branding”, and which can’t. For example, the front grille of a car is, in most cases, a branding element – if the car manufacturer wants to be recognized by this shape. A piston inside the engine, however, looks mostly the same in all cars, as the laws of physics bind it to have a certain shape to deliver the best performance. Therefore, the shape of the turbine is NOT an element of branding.

Not everything a company does is branding - only what it does with the intention to be recognized. This should help us call a spade a spade, clarify vocabulary and know when we advise on business strategy, when on branding strategy, and what the relationships are between them.

Clarity of speech: As brand professionals we should avoid using “brand” in instances where it doesn’t apply, thereby reducing clutter and clarifying meaning. For example, knowing exactly what a brand is should help us refrain from using it as a metonym for “company”. “Brands should invest in…” – no. Companies, business units or people invest. Brands cannot invest. Paradoxically, this should not lead to a decrease in brand importance, on the contrary: our definition implies that everybody brands, whether they like it or not. Every entity performs intentional actions in order to be recognized. The choice is therefore not whether to brand or not to brand, but to brand well or not to brand well. And that’s where the art and science of brand strategy and management comes to shine.

Clarity of method: Brands do not exist on their own, outside of the entity creating them. Good branding should therefore pay special attention to both the entity and its stakeholders. A company, for example, creates countlessexpressions intended for recognition. Products, services, processes, rituals, design elements, sensorial experiences – all are, or can contain, branding elements. Leaving any of them to chance presents an inherent risk. It is preferable to have a system to manage these expressions. Brand creation and management should take advantage of the latest science on signaling, information processing and decision-making, to create expressions with highest efficiency and impact.

To recap and keep top of mind as you go back into your day to day, thinking about how to best leverage your brand or the one that you are responsible for:

A brand is the sum of expressions by which an entity intends to be recognized.

A definition should just tell things the way they are – what we then build on it is the important part. Loading our expressions with meaning is what makes or breaks a good brand – and often, a good company. More on that in our next article, brands and value.

References

Some of the content can seem bewildering. Below a list of references, for your information, entertainment, or outrage.

(1) On the various ways in which brands are described:

https://www.humanisethebrand.com/best-quotes-marty-neumers-brand-gap/

http://www.drypen.in/branding/brand-is-a-living-memory.html

http://www.ogilvy.com/events/cannes-2015-events/brand-as-interface/

https://www.deeprootdigital.com/blog/what-is-a-brand/

http://brandchannel.com/brand-glossary/brand/

A metonym is a word used instead of another word, e.g. “the White House” is a metonym for the “Presidency of the United States”: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/metonymy

For example: “A brand is a promise. Strong brands have relevant, differentiated and credible promises that they keep.” If a brand is a promise, how can it have a promise? http://www.dolphinbrandstrategy.com/whatwedo.html#brandwhat

(2) On economists being wrong:

On branding people not being trusted

https://hbr.org/2017/07/the-trouble-with-cmos

(3) Branding probably began with the practice of branding livestock in order to deter theft. Images of branding oxen and cattle have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs, dating to around 2,700 BCE.[9] Over time, purchasers realised that the brand provided information about origin as well as ownership, and could be used as a guide to quality. Branding was adapted for use on other types of goods such as pottery and ceramics. Some form of branding or proto-branding emerged spontaneously and independently throughout Africa, Asia and Europe at different times, depending on local conditions. Seals, which acted as quasi-brands, have been found on early Chinese products of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE); large numbers of seals from the Harappan civilization of the Indus Valley (3300–1300 BCE) where the local community depended heavily on trade; cylinder seals were introduced in Ur, Mesopotamia in around 3,000 BCE and facilitated the labelling of goods and property; and the use of maker's marks on pottery was commonplace in both ancient Greece and Rome [10] Identity marks, such as stamps on ceramics, were also used in ancient Egypt.[11]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brand#Etymology

(4) Pavlek, 2008;120

(5) Occam’s Razor: 11 Original: Non sunt multiplicanda entia sine necessitate http://science.howstuffworks.com/innovation/scientific-experiments/occams-razor.htm

Zur Übersicht

Drucken

Drucken Per E-Mail versenden

Per E-Mail versenden Auf LinkedIn teilen

Auf LinkedIn teilen